Everything is Regenerative.

Sensitivity Warning: I am speaking to rape, emotional abuse and death in this essay. Please be gentle with yourself and use discernment before moving forward with this reading, you come first x

Merry May, everyone.

there is porridge on the stove

willows weep

as miss nina sings

chords that could coax

a grown man

bring him

to his knees

for spring is here

and the sun is blinding

Pluck it from the

Skies

hoard it like

a white king

I find myself

In the breeze

find myself

In the symphony strings

beautiful cacophony

no ambition

but to lay around

and

dwell

for spring is here

and no one

can

bind me

no one

can

exploit me

no one

can

rape me

[this space is intentionally left blank]

I,

travel far

in this backyard

farther

than fulani scalps

bury myself

where ever the

wind takes me

for spring is here

and sweet raven is

well fed

zigs drifts

into rest

as i pull apart

my limbs

for my morning stretch

as my

mothers porridge

cools on the stove

and

ashley sniffles

in her sister’s

bed

for spring is here

and no one

can

bind me

no one

can

exploit me

no one

can

rape me

no one

can enslave me

for I am, wild as

the wind

and even more, my word is binding

amen

Everything is regenerative.

[Part I ]

I like octopi because they have nine brains. Each tentacle has its own nervous system, inhibiting its very own (interdependent) autonomy.1 I like to think of my interests and mediums that way, independent of me, moving and wriggling themselves into shapes and tiny sea caves unbeknownst to me— self-sustaining and trustworthy, I let them have their own way to get to where they desire and in return, they serve2 my goals while simultaneously serving themselves. My love for octopi comes from my interpretation. These mostly independent sea creatures have collaborated, co-conspired, with evolution to become their own highly-organized, interdependent organisms. a full-fledged functioning commune all within their own limbs. I look at them with quiet admiration. I cant help but to covet the ways they’ve collaborated with nature. They are lonely creatures only for those who don’t recognize all creatures as cellular communities on their own. We are all a set of bustling cells, regenerative and interdependent and for a blip of time, when we take the care to extend ourselves through community, through friendship, through blood and tears, we connect, our bustling set of cells to a whole other host of cells in the other.3 When I imagine the inner workings of my body, I close my eyes and I see my city, on the southern ends of Florida from a hawks eye view — the lights are blinking, the cars are moving, and all of us, are bustling. I gift my vessels and neurons their own autonomy, with my city in mind, and the sight that from above, on this flight, Miami breathes like a scarlet red-throated reptilian. I break my organs down and gift them minds of their own and I play pretend until eventually it morphs into a reality— a sure reality, my reality. It makes me think of Little tree’s interpretation of the spring bank as a boy. 4

With that knowing, I hold myself with the clarity and understanding that I have a host of cells, a city to thank each day when I wipe crust from my eyes. It took a lot for my body to draw breath today. It took a lot of war and bloodshed for me wake up in my right mind. My mother has been telling me the same morning meditation since I can remember:

“Don’t forget to thank Fada God that you wake up inna yuh right mind this mawnin’”

I break myself apart until I am looking back at myself, at my cells.

It is the intuitive practice of commune and the life force of self and the ones who reach to me, as I reach for them, that leave me in unbridled awe. I sit on the highly organized cellular process that is given to my life, to all life, and I spring my questions, my theories, my grievances and my pain from that centre. From that understanding.

My last story on my Instagram, before I got suspended late September 2022, I was speaking up on my rapist, Skinny Macho. I can’t remember exactly the story that did it but I do remember the feeling firming itself inside of me that I’d kill anyone, dead, if I ever encountered another rape.

I had undergone numerous rapes and sexual violence, but this one felt different. The night I was raped by Skinny, I had done it all right in my mind. I had used all the carefully collected jargon from the pastel-painted infographics, instructing how to express firm boundaries concerning non-consent. Somewhere sly, in the still waters of my brain, I had chalked up all my other rapes and sexual assault to simply “not communicating clearly enough.” That night, however, I had been open, and stern repeating:

“I am not in the place to have sex.”

I used exact language so there could be no confusion. I did not want to have sex as I was flirting with the idea of a passage of celibacy. I was on my island, during a global quarantine, fresh from my Mama Vera’s funeral and in the midst of an abusive relationship gone even more sour. So, I did what all the infographics said to do, and I went to bed, confident now that since I had firmed up! and didn’t choke or bat away from my non-desires, I was on my way to a good night’s rest, in the massive California king size hotel bed, in the sterile white Geejam Suite on the last day of the most unprecedented year yet, the bastard year that was 2020.

I did it all right and I still woke up, being raped.

The realization that I could communicate, use all the buzzwords, say it clear as day and still be raped emptied me, almost immediately. On January 1, 2021 I woke up, confused and near climax. Seconds later, I orgasmed. Fully awake, I shot out of bed, clumsily climbing the pristine steps towards the upper-floor bathroom, there were no bodily functions to relieve but my body took me there as if on autopilot. The body was looking for a quiet gape of time to understand the devastating pleasure that had just occurred. Distraught and still doused in sleep, I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror and realized, I couldn’t find my reflection. I was a ghost of a person most of the year, following two funerals and a tumultuous situation-ship. I stayed in Jamaica after my great-grandmothers funeral because my mother and father were back in the countryside and I felt more grounded to be on my island with my parents somewhere off in the distance, even if my latest bout of murky waters re: love and friendship that had gone disastrously wrong was looming somewhere in the capitol during the height of COVID-19.

It was the end of a bastard year, the end of a bastard love and I was at the tail end of my 24th year and completely nowhere to be found. I had never seen blankness look back at me the way I seen it in that moment, in the early hours, at the Geejam hotel. It was quarantine in Jamaica, the curfews were strictly enforced and my airbnb was on the other side of a strip of road that felt like it segregated the locals and the tourists. There was the colonial cobble-stoned relic, perched between, sitting dignified and glowing a ghostly white, inappropriately with pride. I drove by it many afternoons in a contemplative daydream, quietly sitting with hazy contempt of the romanticized relationship that had to dance with our Brutish-British-colonial power to have this building, this architecture with such a painful past, still standing. I shot to different timelines, feeling caught in the past, and maybe somewhere out there, in our very own present currents of chattel-hood.

I liked to be on this side of the town, with the locals. I wasn’t local to Port Antonio, Portland but I was local to Rowes Corner, Manchester, a red-dut5 district in a dust bowl valley. My mothers, mothers family had lived there for hundreds of years in the southwestern corner of the island, on the same handful of acres of land that my great grandmother’s, grandfather had stewarded and handed down to us. Mama Vera was born on that plot of land. Clara, my great grandmother’s, mother had grown into herself there, birthing Mama Vera down ah yaad from our Logwood home. Winsome Juliet, my grandmother, Desireen Claire, my mother and me, Zoé Denessa, all spent our childhoods in and out of the lands with Alligator pond, a legacy sea port, out past our land. You could see the sun setting on the shoreline from yaad if you stood out by the back porch. I watched the sea many afternoons in serious contemplation growing up as a child.

I didn’t share the same sentiments as most of the foreign tourists. Having grown up between South Florida and the poverty-stricken countryside of my forefathers, Jamaica wasn’t strictly beautiful or paradise or charming or even comical. Jamaica was also suffocating and a sensitive place for me as it was the home of the unmentionables that plagued my childhood and my family. The newly found crew I had hitched on for the last couple of months weren’t exactly my normal choosing for acquaintanceship. They were overwhelming cis and nauseatingly heteronormative but I was all but doxxed from one of the only queer groups on our island and deemed delusional by the same woman who had spent the last year and some change, begging, pleading with me to compromise, to not leave, as did I, with her. At the beginning of my trip, she attended my great grandmothers funeral with me, slept in my childhood bed, and walked the same curved roads of my childhood kingdom. A few days after the funeral, we broke things off, again. I was of course, broken up about it. I was in the trenches of grief for my best friend, Jawni and Mama Vera. I started to turn the idea over in my hands that maybe I had made it all up. Maybe I was always the only one in love. This was the second time following a funeral where we had broken up. The first time was during Jawni’s passing.

Earlier that year, 2020

I had broken things off, firming up that if we were to keep things platonic she could no longer call me “baby” on the line and that I would need proper space to decontextualize our highly emotional (and volatile) friendship. With time, I knew that I could. I was approaching a more expansive outlook on romance, freshly baptized from the scriptures written out in Pleasure Activism by Adrienne Maree Brown. I was a bouquet of petals opening to the great big sun of understanding that love and partnership could unfold in a way, rid of the colonial textures that coloured dating with possession, ownership and leaky remnants of chattel intimacy. I look back at my first encounter with the text fondly. I found myself in the pages and started to realize that I had been loving in a polyamorous framework for as long as I could remember, making sense of my precocious love life as a teenager.

I was met with tantrums, that if I could leave then I didn’t really love her. The following day, after I followed through with breaking it off, following relentless pushback, it was Gabe’s birthday and we all packed ourselves into our cars and celebrated by the beach. My friend at the time, Amandla, was given a pre-listening link to Kelela’s, still untitled, and greatly anticipated album, I believe it was via a dropbox link. After the sun settled, we all went back to West Hollywood, nestled ourselves into Isa, another former peer, childhood home, ketamine-in-hand and melted into the living room couch, listening like a pack of monks to the demo tapes that sputtered through the speakers. Earlier that day I had gotten an irate message from Kirsten. She was predictably upset that I was discussing our emotional end with our friends. High and swaddled by the presence of my friends (at the time) I decided to respond the next day. I listened to the sneak peak, eagerly; mostly satisfied by the potential of the demos. Soon, we all went home, grateful to Amandla for letting us listen and I went to bed, coddled and pacified6 although I knew I would have to mull things over with Kirsten before I could take a deep breath.

The next morning, before I could reach out to Kirsten, I got a strange phone call. It was Vanessa, a friendship on its way out, ringing me after a near month of us not speaking, to say that Jawni had hung herself and was in critical condition. I was shocked, then angry, convinced this was another one of Jawni’s tricks and that she’d pull through and I’d all over again, talk sternly to her about her actions and she’d all over again, tell me to stop treating her like a child.

It was a reoccurring bit for us two.

When I hung up on the call, as if on duty; I set up to dial and respond to the messages from the day before. I got on the line with Kirsten, exasperated, quickly getting some words in that I was not trying to embarrass her or expose her but that it was a boundary I made with myself to not keep my romantic life private from my friends, as I found myself in a physically and emotionally abusive relationship only a year prior with my tragic first love by keeping quiet. I almost lost my life in that relationship with their hands around my neck and when I called over my friends, embarrassed and sore from our final blow out, I made a promise to not hide my relationship, no matter how embarrassing, to my family or my friends. Kirsten was fiercely sensitive when the prospect of her being left presented itself, she seemed stuck in her own ouroboros of sorts, deeply fearing abandonment and the stakes she bargained to lose of who she’d have left if I went my own way and figured myself with others who could understand how to love me. I watch her not want me while simultaneously struggling to stuff down the persistent softness she felt for me. She carried on, insisting that we keep things private. I soothed as much as I could and although she held the belief that we should keep this dilemma to ourselves, that it was just as much her business as it was mine and I had no right to speak on it with my friends: we rejoined one another at the centre (the middle point of a sphere) of it all, despite our differences or the myriad of outlooks, the one thing that rang true for the both of us was that we deeply cared for another and simply were in no state of heart to let one another go.

After 2 hours of calming things down, we found ourselves, again, on the line, baby-talk ensued and guards flailing. When she asked me what I was planning to do that day, the previous phone call snapped back into the forefront of my brain. I had been so consumed with the assignment of calming her down that I had forgotten that Jawni had hung herself and was on life support. Immediately, I collapsed. A blubbering spud on the phone, my roommate and then best friend, Stazi and our friend, Maliyah, came in to investigate. I found myself in shock, repeating context-voided lines out of my confused thought stream, favoring a broken record, not being able to catch my breath.

We were still on the line.

She told me to go and she’d be there to talk tonight. I had a photoshoot in the valley that day— one I had been planning for weeks, a personal shoot and the second time using myself as the talent to flesh out my creative direction. I was exhausted from commercial modeling and photographing industry stiff and painfully unpracticed models. I was at a crucial apex in my art practice. Capital had spread, and hooked, it’s poison-dipped nails into the medium. I was beginning to need to prove to myself that I still held the eye that got me into photo-making in the first place. I decided to go through with the experimentation as Jawni and I had notoriously shot together while holding our turmoil. It was our style. I bargained that by the time we wrapped, I’d get the promising phone call that Her, my reoccurring muse and Me, her quiet capturer had pulled through, at the very last moment.

I had never had a muse quite like Jawni. Her movements haunted the camera, leaving trails of blur following her arms and legs. I was lucky to shoot, and be shot by Jawni throughout the years. We were both good at disappearing. We drove up to camp out by Sequoia Forests, ran fast in pumpkin fields (Rinko, my absent roommates dog, in tow), walked quietly side by side in fruit groves a few hours north of Los Angeles, both in our own respective inner worlds. We would go east to Tao’s compound in the desert, an unrecognized prince with royal bloodline from Italy, when either of us had a fallen out with our doomed lovers we had innocently chosen as the “one” at the time. We even went as far down south to a Mexican rainforest in Veracruz, where we were irritable about the Mexican Military escort brigade that followed us, becoming an obstruction for our normally nude exploring and photo-taking. The peer who invited us to her Veracruz home and the rainforest was the daughter of a politician who was firm about us having protection as we drove around the state. Jawni was my teacher when it came to posing. She was patient when I was in front of her lens, tender and quiet. The same way I was behind the camera body. I blossomed under Jawni’s eye, finding myself contorting my body how I’d envision she’d use the space around her. She gently encouraged me to play with the camera whenever we’d switch roles. I used all of our quiet practice that day in Ryley’s backyard, on a sweltering hot day, out in the valley.

The week went by quick. It all happened like a gust of wind. The promising phone call never came and I lost the bet, one of many bargains I’d lose when it came to a dying loved one.

Jawni was taken off of life support. We rode up to see her for the last time as she laid deadly still, tubes all through the openings of her body. She was shallow breathing; swimming through a near brain-dead coma. A few days later, we rode up to Bakersfield for the funeral, borrowing either Tal or Amandla’s car, I can’t quite remember who offered. On our drive back, early into the long ride home, I pulled over, overwhelmed by the new reality and by the Reggaeton track swirling in the car’s speaker. I couldn’t stand the drums, it wasn't the time or the place, I thought. I pulled over to a sweetgrass-looking field that was sunburnt a sweet tan, directionless, as if on autopilot. It reminded me of one of Jawni’s and I roadtrips.

It was one of Jawni’s favorite color palettes, she said it reminded her of her soul.

I climbed out of the driver’s seat and tumbled toward the field and cried with a crushed Ama, close by. Vanessa looked on from the car. I had never been so happy to see drought-stricken fields, to look at the dusty purple-grey rolling mountains in the distance. California was my playground and Jawni was one of my first friends when I moved out to LA, a jaded FIU graduate with a sully bachelors degree in hand. California was our playground.

Kirsten stuck through that week.

Although I had initiated space the day before the news of Jawni’s suicide, she nursed me, I, in Los Angeles, her, in Toronto, letting me drift in and out of sleep and expressing concern on the phone the night we went to see Jawni’s spirit still in her body. I came back onto the line after the hospital visit, unable to speak without slur because of a particularly strong xanax pill. About a week had passed and the dust was settling. Kirsten and I were falling into our familiar pattern of spending way too many hours on the. I became anxious, feeling like I was in the midst of a ticking time-bomb of comfort. I was thankful to have her in such a desperate time of need but with the pesky knowing that our opposing definitions of romance and friendship were still wedged like over-ground matted roots beneath our feet. I reminded her that now, more than ever, I needed us to take space because my friend was dead and I couldn’t have anything as tumultuous as our unpredictable relationship in my brain while I figured out this new life, a life without Vidal, Videl.

She told me that I had used her for comfort and that I was once again, only prioritizing my needs. She then proceeded to block me. We stayed blocked for a month or two, enough time for me to feel proud that I had stuck to my word in letting us go for the season as I cut and grow with this new world.

This time around, in Jamaica, her anger was palatable. She was upset, convinced that I was running around speaking on our unmentionables, telling others that we were more than what she deemed we were. The same arguments circulated. The truth was, no matter how I laid out the story, or tried to emphasize that we were just friends, others would look back at me in suspicion of Kirsten’s outlook re: our connection. Many were convinced that I was dealing with a person knee deep in their own denial, I agreed with their interpretation. If I turned to leave, she’d threatened to collapse, bringing up that she had not opened up the way she opened up with me with anyone else. That I was the only one who she was this open with about depression and love and despair and all the things you whisper about to a loved one. I was consistently reprimanded for having as much friends as I did and told it made me behave “selfishly” when I didn’t think about how a separation between us could affect her day to day. I was the only one who knew her, the hidden her, she deemed me her favorite person.

If I hoisted myself up by my bootstraps and stayed in the coffin she carefully constructed for us, we could stay, rigid and unmoving in our dilemma until our next eruptive blow out. She preferred to pin our friendship against a corkscrew board like a tempered scientist pinning butterflies wings to hoard for later, always good to return after another failed romantic endeavor. We argued loudly about it. I was fed up with being the circle back. I was good to return to when she’d find out whatever man she was dating at the time lied to her or when she walked into rooms, catching them mid-act, stepping out on her. Her rehashing the disappointment over the line would cause another fight because I was confused on how she could be so upset about the infidelity by her partners when she was emotionally stepping out of her relationships with me, throughout the years. When she confessed that she was in love with me it came with a historical timer because she was sure to take it back when our conversations became heated. We’d argue for hours, yelling, cussing, hanging up on the line, calling each other back. “Just answer the phone, Dog” blocking one another; returning to the crime scene via emails. We had ended it countless times, and cried to one another about not being able to get it right, countless times. I watched us try to figure a way for the feelings shared between us to go no higher than where Kirsten could control them and where I could subdue them which only angered me, feeling like a puppet on an impossible string. She did want me to go, could not handle when I found myself in love with someone else, which my polyamorous nature made completely inevitable and she did not know how to handle the emotions that came when I stayed.

On our island, we both returned to Jamaica during the height of quarantine, a chuckle-worthy irony as we had spoken countless times about meeting one another on the isle once the bans were lifted. I was in constant defense with my friends that she didn't hurt me because she was malicious, that we had two different definitions of romance and friendship and because of that, I was touchy about my friends calling our situation abusive. I shut down Jenelle and Jaira many times about me resembling my former appeasing mode that surfaced when I was in too deep and forfeiting my needs. When Tal tried to interject, I brought up the realities of what it was to be a dark skinned femme and soon enough, my friends stopped interrupting me and I would go through the vicious cycle, each time coming back wet-faced and crippled, with my tail between my legs, by the relationship. They were the well-meaning kind of friends, that stuck through and didn’t abandon you when you found yourself stuck in a revolver of a love crime waiting to happen. They’d take me in and nurse me just as they afforded me my autonomy to let me carry on, figure my own way and consequently, as painful for them as it was for me, watched me walk further and further into a plot of quicksand each time Kirsten and I reconciled.

I like to think of bonds as worlds. Love as spheres. The tiny spot we meet one another can have a setting. With Bun, me and Jenelle’s pet name for one another, the space looks like ancient china, 700 BC. It’s a smoky forest and she’s a flower lily thats never been touched. I’m the chartreuse-tinted, jade enshrined water she sits in. She’s also the opaque morning mist that brushes against my waters. We are interdependent and present in each others lives not out of obligation but because we want to be, because they is the sheer desire to live this timeline, side by side. The understanding we have grown over the span of 16 years has assisted me in using discernment for my romantic relationships, now. Not then. I question myself “Would Jenelle ever treat me this way?” and if the answer is no… I know I have to start reconsidering the relationship. The understanding between us, making itself clear to those around us, makes itself known that our love shared is transcendental, bigger than any epoch, time or distance. I have a voice note on my phone from a sleepy Jenelle assuring me that our friendship has traversed time and space. It lives on the track Wi-Spa, distorted but firm. It was that way since I was 11 and bun, 13 years old. I didn’t know back then but the love stewarded between us has proven to be a compass for me. I saw our beginning in a vision back home in Miami after coming down from an acid trip, absolutely peaking at III Points, 2019 during James Blake’s set with my gang of best friends.

Some people are a room.

just four walls but there are mirrors in place of cement; so we go on and on— timeless, in perpetuity. Some loves are a small garden; good to step in and breathe the blossoms of the seasoned bloom like the one Toni Morrison describes in Beloved. Some spots are wide pastures, like the one Baby Shug’s calls everyone to come worship in to shatter their grief.7 Some spots are stifling, some are open wide. Some are breeding grounds for creativity, understanding and growth;8 it depends on the person, depends on the love. Some are a cocoon, proving to be good for incubation or loving in between forms.

Kirsten was a web.

Emergence felt like death but the whole time it was new life crashing into me, untangling me from a 2 year sabbatical with a foolishly insidious definition of love.

For that time on that island, no one knew about our ruptured past.

We were better off strangers.

I dealt with someone who had consistently hung their depression and suicide ideation over my head, as to explain why I was selfish for needing to leave a relationship that was not meeting any of my needs, rob me of even the reality that it, we, happened. She spun silk thread, missing a lot of loose threads, to unknowing queers on our island and over the social scenes in different cities across the world, that I, was a disgruntled ex-lover, obsessed with having her to myself, lightyears from the framework I was dedicated in imposing upon us to much, much pushback. I wanted any romance existing in a sphere of its own, without possession and ownership. It was hard for Kirsten to wrap her mind around it. When word got back to me of how I was being framed, it use to freeze me up in public, horrified and slightly offended by the mischaracterization but I am here now, years later, speaking on my contesting reality, tying up those loose ends.

I was meant to sleep on Rae’s couch on the last day of 2020. Skinny insisted that he wouldn’t be able to have sound sleep with me crashing on the thinly-cushioned day sofa while he had a California king size bed at his hotel suite.

In that moment, he sounded like a friend.

I was apprehensive, recalling that the first time I had met Skinny, Kirsten was by his side. I was already in so much shit; her anger echoed all over our island, it felt like the last thing I needed was another reason for her to despise me more than she already did. She already had numerous qualms with my sex life, deeming me too precarious, too fluid, too loose, another reason why she couldn’t trust her feelings for me. She regularly oscillated between indulging in her love for me and chasing away the knowing when my polyamorous approach reared it’s inconvenient head.

There was chemistry between Skinny and I. Nothing to speak of for very long but the appropriate amount of chemistry I can muster up for cis men. I thought he was funny and a bit goofy-looking and I liked his hair. We had been exchanging eyes and subtle touches throughout the night and it felt nice to sit on his lap in Jeano’s packed car on our way to the bar across the segregationist strip. It felt nice to bubble and hum with Bafic and him over a Snoop and Pharrell tune. The shrill “Can I get more thrills?” from the ladies on the back vocals played gingerly as we set out for the last night of the worst fucking year of my life. I wanted to get blown. To have a drink and hit some weed. I also wanted to capture us singing-along to the track but when I went to record it on my trusty voice memos, the notification sound gave me away.

Bafic laughed at my clumsiness, I laughed too.

It was sweet to hang out with these London foreigners amidst all the bowels of shit I had found myself in that year. The thought has crossed my mind that had Skinny not rushed the unfolding of our subtle attraction, we could’ve spent a few weeks treading lightly with one another in the tropical heat.

The morning after— Skinny apologized, sensing that he had gone too far. I accepted the apology, unaware of how that night would touch every cobwebbed corner of my life in the 2 years to come. We spent the rest of the morning, limbs intertwined, in and out of sleep as the movie ‘Hills Have Eyes’ played on the Hotel flat screen. Skinny was better at cuddling than he was at listening. Rae swung by and I walked to meet her in the hotel veranda where they had a bar and seating area, overlooking a luxurious pool. As the distance between us and Skinny’s suite stretched out more and more, I jokingly offered a glimpse into my night, announcing playfully “ I guess I got my first nut of the year, I wasn’t expecting it but..” the words turned to goop as soon they left my mouth. I couldn’t finish my sentence.

Something was not right.

We walked through the beautiful stoned pathway, lined with Xamaycan flora and fauna that led you from the hotel to the main road— the garden just reaching enough over you to block out the harsh sun.

It was an obnoxiously, beautiful first day of the new year. I felt a pang of optimism surge through me, even posting a photo with a caption “charging 2020 to the game ! 😇” Things felt promising. It was after-all a beautiful day on my island. Although I favored the walking dead on the television screen earlier in Skinny’s hotel suite, I was for the past month climbing waterfalls, peeking my head into caves in my birthday suit and retracing the steps of my indigenous ancestors on my island. I thought about Miss Mac, my Afro-Indigenous great grandmother, with her famous dangling thick braid settling past her hips and wondered about where her great grandmother placed her steps. I wondered if I had stepped foot onto any of her secret pathways in the time I spent on my island, tumbling through the worst depressive episode of my life with an oppressive tropical beauty threatening to drown me out completely.9 When the crew suggested that we all go to the private beach to lay out, I followed with no hesitation.

While laid out, I could not get my blood vessels to relax into my body. There was something making my stomach turn and twist. Eventually, I started making my way to leave early because of the knot in my stomach that unabashedly writhed itself against my lower guts. As I walked out the gated beach, I bucked up on Bafic and Skinny, walking over to join the rest of the gang still on the beach. I made sure to play it calm, offering Skinny a direct look in the eyes a couple times, trying my best to convey that I was cool on it and had already let go of the previous night. I had not deemed it rape until a couple months later when a peer told me that Skinny had a history of waking femmes up with his fingers where they had no permission to be. I walked to the street, hailed a taxi, crossed the bridge, passed the colonial relic, and tumbled into my airbnb’s full sized mattress with such conviction, I felt like I might not ever rise again.

In retrospect, when I said that I would kill the next person who tried to rape me, I was pleading with all the proposed realities of my future to withdraw from the prospect of ever being raped again. When I posted that story, it wasn’t to incite violence, it was me understanding that if I suffered through another rape, I would either have to kill myself or the person prying between my legs. I am quite serious when I say, if I were to find myself waking up on the edge of orgasm, after approximately 10-15 no’s for the night, I could not do this whole reckoning again, with somebody new. I find it hard to kill bugs, cupping termites in my Aunty Tricia’s South Florida home to carry outside to the garden and I grow queasy imagining myself playing God and taking breath from another human being.

But I was on my knees for 2 years straight following this rape and I cannot fathom losing my body or even worse, my spirit, again, to another sexual assault.

By Instagram guidelines though, I was inciting violence on my account as I encroached on a hypothetical quest to figured out new direct action to take when it came to having my bodily autonomy stripped away from me. I was exploring the topic of killing my hypothetical rapist, mid-act, if I ever woke up to foreign phallic members prodding, probing to find my clit. I concluded I’d accept the consequences of my actions and keep a stiff upper lip the day of my sentencing. I saw my life laid out before me, the headlines read “Girl kills her alleged rapist MID-ACT,” even more sure that my gender identity would be swept under the rug. In response to the prospect, I made sure to write my will and testament, at the tender age of 27 so I could never be dared buried in a dress, in the side-yard of a church or called a woman on the funeral program.

Anyways, I was promptly banned from my Instagram account the following day.

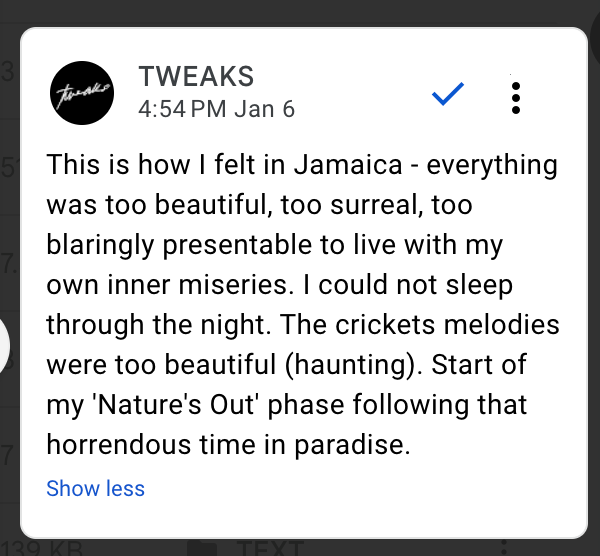

In the weeks leading up to my month-long ban, I had just left a family trip with my closest friends in London. We were celebrating the baby of our groups birthday, sweet Olivia. We saved, for months and I, planned for months, using the skills I had picked up from self-producing my editorials, music videos and campaigns for my alias, TWEAKS. I used TWEAKS for the first time amongst my friends, offering them insight on the major difference between Zoé and TWEAKS. TWEAKS was efficient; TWEAKS was careful, TWEAKS was a planner and only showed up on google meets and on set. I brought TWEAKS out to ensure that we got Olivia to carnival, her only wish for her day of birth. I made it my project, same way Videl became a child of mine after major loss. It was the first carnival since Covid and we were eager to feel the buzz of the crowd. We held porch meetings, I drafted budget sheets, compiled airbnb options, created colour-coded folders designated for passport information and covid preemptive paperwork. I ran a tight ship, asking for everyone to have their materials handy and communicate any changes in a timely manner. Eventually, the family vacation came. One by one, we all flew in from our respective corners of the world and into a humble airbnb, a goldilocks fit, for the six of us. Jenelle and Clinton took a room, Donovan and Myai took the pull out bed and Olivia and I, known for our distracting giggling, and banned from our go-to sushi and beer spot, Zencu, a year before for laughter too disruptive, took the second room.

It was a homecoming each time one of us arrived to our Airbnb in Chelsea. We chuckled about the irony that our airbnb was located in Chelsea and Chelsea, who cancelled last minute as did Marissa, and Bethlehem and Terrell, was not there to see it.

But we were together.

The core of my support system. Between all of us, we’d known each other for approximately 5-15 years, Donovan being the last to make family, only 3 years but feeling like the same time spent. We were hungry for one another, the way dogs look up, stiff-necked and then disappointed with their chins on their paw, waiting for their always late human. Or, the way as a child you became sad, all of a sudden and all at once, as the realization dawned that it had been a few weeks since your aunt and cousins came by for Sunday dinner.

These were my forged cousins.

The trip served as sort of a balm for my loved ones and I. At the time, Jenelle, my best friend of 15 years, had lost her brother, Courdel to cancer a few months prior. Myai, my best friend of 5 years, was dealing with her mother’s terminal illness coming to a heartbreaking end. Terrell, a newer friend of around 2 years, had recently been physically assaulted by guardsmen at a local night club in London a week or so before and I, I, as expected, was reeling in from the tumultuous ending to my drawn out situation-ship where I uncovered multiple dishonesties and non-consensual truths towards the end, coinciding with Courdel’s final days, juggling the feelings of finding myself in love and deeply involved, all over again and navigating how to coax my spirit back into my body following a dissociative year and a half, spasming in and about when I was touched for a moment too long by others. I was set to speak to my rapist, face to face in Rae’s London flat, the following week after carnival. Terrell became my designated emotional support when Clinton, my best friend of close to a decade, couldn't extend their trip to make the ominous meeting. Terrell was to be a buffer for the raw bone exposed which would be grinded against when we all came as one in the London flat. They stood by, serving as a witness and minutes keeper, as I watched my rapist, grovel in his despair and wipe tears from his eyes.

I could feel both of our pain in the flat.

Tyson, Rae’s strikingly affectionate cat, unknowingly soothed as he gracefully slinked around the flat, cozying up and going about his business on his own accord. Terrell was dumbfounded by the space I let form for Skinny’s pain, warning me to be careful of letting him speak as much as he was about his grief and insisting that I prioritize my feelings. I was prioritizing my feelings though by letting his side colour in the missing details. The one thing I have learned from tragedy is collecting as much details, in a timely-manner, so I can properly mourn in the comforts of my my own company, in gentle retreat with accuracy and patience after the fact. I assign the personal and look for the impersonal when I find myself at the receiving end of harm, to know what is mine to rage, grieve, mull over and what is theirs. Theirs is the abandonment issues stemming from a neglectful mother, theirs is misdirected grieving because of their own shortcomings or insecurities. Theirs is their own poor definition of consent. Theirs is their own repression of their own dealings with rape and abuses. That is not mine to hold nor internalize. That is theirs.

I like to gather every minute perspective so I can sleep through the night, without questions plaguing my mind of what I should’ve asked or what I should’ve vocalized. I don’t believe in using the word “should” so I have to act, each time with integrity as to not encounter what I should have done. What I should have said. I let there be space to hold my pain, and his, because I knew we’d both need to hear each other if we, but more importantly, me, were to ever move forward. I let him colour in his details so that eventually one day, I could close this situation, shut with firm boundaries in place and no room ever for a circle back. I didn’t deem Skinny evil or a monster, I deemed Skinny a person with a poor definition of consent. I was starting to understand that so many people around me, myself included, had grown up with a lousy definition for what constitutes as consent. When I recounted our accountability meeting, with the accountability contract10 I had drafted in the uber on the way to Rae’s flat, a new friend, Abdou, was vocal about being mostly unimpressed by Skinny’s display of emotion and offered the prospect that Skinny was taking advantage of the empathy I worked hard to employ amidst tragedy. This was my first time feeling pulled by tears because of my rapist’s own going ons. As I was in flux, he was also in flux with his mother battling cancer and grieving a loss loved one, Virgil. It made me mourn for myself and for the night I was raped as I, at the time, was in deep flux while Courdel battled cancer across the pond in Port St. Lucie, Florida and I grieved my dead friend, Jawni and the capricornus matriarch of my family, Mama Vera. I understood what he meant when he said he felt like a shell of a person. I could feel the grappling effects of death touching him in Rae’s flat. I knew how he felt because I had felt the same only a year and some change before. I’ve cried blood when thinking about all the things a body has to process with a terminally ill loved one, a recent suicide of a best friend, a death of a matriarch, the explosive collapse of an abusive relationship and a poorly-timed rape.

I find myself stuck in the throws of unwavering compassion for myself and how I chose to deal with the cards dealt. At 28, I wrap up my 24 year old self with unwavering balm and remedy. I look at my under 25 year old friends now like children. I am terrified when they call me with their bouts of abuse and tragedy and love and death. I vocalize concern often when they speak on any confusing relationship, friendship, situation-ship that resembles the web that was Kirsten and I. My friends and I are in flux, together. My rapist and I, were in flux together. It dawned on me, in Rae’s London flat, that we will always be in flux with one another and even so, we have to still choose to speak up on the harm caused because of the crossfire that flux can bring.

I haven’t sat on the words long enough to articulate what it feels like crying tears for the person that raped me and I think that’s alright for now. I won’t dishonor the feeling by desecrating it with language.

Our London trip beautifully came and beautifully went.

Myai’s mother passed a few days after our trip. I dedicate a pause here, to honor Sophia Puente and let go an offering of a studio session at a time when a loved one’s death also had me on my knees.

I love you, Myai.

New Drugs (North Broadway Studio Session w/ Raveena, April 8th, 2021)

I let my suspicious rise; heart race as sirens go wild. I’m feeling like a caught convict. Can we leave this fight for the men outside? There’s a war outside. Fireworks break the night sky; I shut my eyes real tight. Feeling like a kid with no ties. My sleeps broken in three’s; green tanks crowd my street.

Jawni’s got me down on my knees.

But, these pills, these pills help me stay sleep. And this love, this love can’t be no good for me. But in these walls, with the red light on. Yes, these walls with the red light on. I’m safe in these walls with your voice on the phone. Yes, your voice on the phone.

So, let’s leave this fight for another night. Let’s leave this crime for the men outside. So, let’s leave this fight for another night.

Let’s leave this crime for the men outside.

The Insane Biology of: The Octopus (Documentary)

Why am I comfortable with using the word ‘serve’ here? No question, it has something to do with the concept of masters and servants, the formerly enslaved. Noted.

The Insane Biology of: The Octopus “In addition to helping establish motor coordination, play in most species is largely needed for social purposes— for establishing social rank, for learning social rules, or for bonding. Due to its complexity, play is considered to be almost exclusive to mammals, with a few exceptions in other vertebrates, like some birds. But the octopus is a solitary creature. It has no social bonds, no social heirarchy. It makes us rethink the evolutionary reasons for play. In fact, much of our idea of intelligence is based on the idea that it evolved out of a social need. For decades, scientist have wondered about the origins of intelligence, and have tried to understand why certain animals evolved intelligence and others did not. The Social Intelligence hypothesis is the often favored hypothesis for the evolution of complex cognition. It’s the idea that intelligence evolved due to the demands of group living, such as maintaining complex and enduring social bonds, deception, cooperation, or social learning.” (Please be mindful of the colonized discipline that is “science” and use discernment when watching this documentary).

“Reckin’ a million little critters live along the spring branch. If you could be a giant and could look down on its bends and curves, you would know the spring branch is a river of life. I was the giant…” The Education of Little Tree, page 56

Red-Dut (Red-dirt) Red mud is the waste produced from bauxite processing. See, Alpart: Jamaica’s Bauxite refinery company.

Higgs, Endless, Frank Ocean “Saturdays involved making our entrances into life outside. We've been in this room too long. Recreation is keeping us self-contained and aware of each other's forms; still and in full strides, just the same keeping us warm, walking in straight lines, talking to sleep at night coddled and pacified by versions of mothers”

Beloved, Toni Morrison “When warm weather came, Baby Suggs, holy, followed by every black man, woman, and child who could make it through, took her great heart to the Clearing--a wide-open place cut deep in the woods nobody knew for what at the end of the path known only to deer and whoever cleared the land in the first place. In the heat of every Saturday afternoon, she sat in the clearing while the people waited among the trees. After situating herself on a huge flat-sided rock, Baby Suggs bowed her head and prayed silently. The company watched her from the trees. They knew she was ready when she put her stick down. Then she shouted, 'Let the children come!' and they ran from the trees toward her. Let your mothers hear you laugh,' she told them, and the woods rang. The adults looked on and could not help smiling.

Then 'Let the grown men come,' she shouted. They stepped out one by one from among the ringing trees. Let your wives and your children see you dance,' she told them, and groundlife shuddered under their feet. Finally she called the women to her. 'Cry,' she told them. 'For the living and the dead. Just cry.' And without covering their eyes the women let loose. It started that way: laughing children, dancing men, crying women and then it got mixed up. Women stopped crying and danced; men sat down and cried; children danced, women laughed, children cried until, exhausted and riven, all and each lay about the Clearing damp and gasping for breath. In the silence that followed, Baby Suggs, holy, offered up to them her great big heart. She did not tell them to clean up their lives or go and sin no more. She did not tell them they were the blessed of the earth, its inheriting meek or its glorybound pure. She told them that the only grace they could have was the grace they could imagine. That if they could not see it, they would not have it. Here,' she said, 'in this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard...”

“How do you share your life with somebody?” scene Her, 2013

The feeling I was feeling reminds me a lot of a piece of text I read early this year by Jamaica Kincaid— A Small Place:

“and no real village with such a name would be so beautiful in its pauperedness, its simpleness, its one-room houses painted in unreal shades of pink and yellow and green, a dog asleep in the shade, some flies asleep in the corner of the dog's mouth. Or the market on a Saturday morning, where the colours of the fruits and vegetables and the colours of the clothes people are wearing and the colour of the day itself, and the colour of the nearby sea, and the colour of the sky, which is just overhead and seems so close you might reach up and touch it, and the way the people there speak English (they break it up) and the way they might be angry with each other and the sound they make when they laugh, all of this is so beautiful, all of this is not real like any other real thing that there is. It is as if, then, the beauty—the beauty of the sea, the land, the air, the trees, the market, the people, the sounds they make—were a prison, and as if everything and everybody inside it were locked in and everything and everybody that is not inside it were locked out.

And what might it do to ordinary people to live in this way every day? What might it do to them to live in such heightened, intense surroundings day after day?”

My highlighted comment the day I read it: